How a life-long work led to a world-wide change

The story of a scientist who defined the future of vaccines

Down with COVID! In today’s issue of Humber Views, we’ll take a glimpse into the world of science and learn how the COVID vaccine was born.

Working through the thorns of refusals and the hardship of scientific work, one biologist’s research not only managed to get published but became a key to the development of the most effective vaccine of our time.

Who is this man? What was his discovery? Find out in the article below!

The man who helped bring us the COVID vaccine

Where it all began

The baby boom of post-war America in the 1950s was a fruitful time for the world of science, giving it many great researchers and inventors. One major name from that cohort is Drew Weissman, whose career has come a long way through many ups and downs on his science journey, with work that eventually led him to the development of the mRNA technology used in some of the most effective COVID-19 vaccines, like the one manufactured by Pfizer.

According to Government of Canada statistics, 83% of Canadians currently have at least one dose of mRNA-based vaccines, and 80% have their vaccination completed.

However, such resounding success didn't come easily.

So let's find out how it all started.

Weissman’s story goes back to the autumn of 1959 when, in the little American town of Lexington, Massachusetts, the Weissman family welcomed a new addition — their son Drew was born.

Even while he was growing up a fidgety kid, playing kickball and causing trouble in the neighbourhood, he always had a passion for science.

According to a profile by Ting Yu published in Bostonia, Boston University’s (BU) alumni magazine, Weissman began his journey as early as high school, taking the top biology classes. That interest gradually made its way to Weissman's further education.

“In college, I became interested in basic science research, studying B-cells that make antibodies as well as autoimmune diseases-that kind of dysfunction,” he says in an interview with Humber Views.

Later on, Weissman studied biochemistry and enzymology at Brandeis University and earned his MD/Ph.D. in immunology and microbiology from Boston University in 1987.

At Brandeis, he had a fateful encounter with his future wife-Mary Ellen Weissman, a child psychologist. In an interview with the Washington Post’s Carolyn Y Johnson, published in 2021, she recalled it was difficult for Weissman to open up at first. But as time passed, he began helping her with schoolwork, and they grew closer and eventually started dating.

First discovery

His academic work eventually led him to working in the laboratory of Anthony S. Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, starting in 1991.

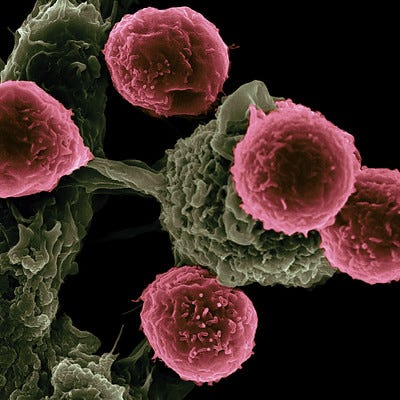

It was there that Weissman made his first big discovery: immune cells that travelled around the body searching for foreign things. He concluded that these cells were a key to understanding how our immune system fights pathogens and could be the basis for future vaccines.

This finding turned out to be a critical point not only in his scientific work but in his life in general. It was the first step on his way to vaccine development.

Soon enough, Weissman had an even bigger platform for conducting his studies. In 1997 he was hired to the medical school at the University of Pennsylvania.

The making of history

By that time, Weissman had made further progress with his vaccine studies, trying to learn more information about a molecule called messenger RNA or mRNA. This molecule teaches our body to make proteins and is necessary for it to function. Weissman was intrigued by the idea of making a new vaccine out of it — one that could trigger an immune response without bringing any virus into our system.

One day, as he was waiting at the office to xerox some articles from a science journal, he bumped into another Penn researcher, biochemist Katalin Kariko. It turned out Weissman wasn't the only one interested in mRNA — Kariko wanted to study it as well.

At first, their work didn't go smoothly. Not long after the beginning of their collaboration over RNA, the scientists discovered it could cause an inflammatory response in our bodies. That's how their first try at making it into a vaccine failed.

“Biotech companies, pharmaceutical companies, academic labs, they all lost interest in our research,” he says.

However, the team refused to give up.

“Kati and I saw the potential that RNA could have and we thought that this potential deserved our investigation. We wanted to figure out how to get it to work”.

From that point on, Weissman and Kariko focused on modifying RNA. In 2005 they had their first breakthrough: they changed one of RNA's building blocks (nucleosides) and discovered it wasn't inflammatory anymore.

By that time, Weissman already had two kids, who were also excited about his findings. When his older daughter, Rachel, found out he was working on something called mRNA, she jokingly pointed out that Weissman must've named it after their family: her mom was Mary, she was Rachel, and Allison was her younger sister.

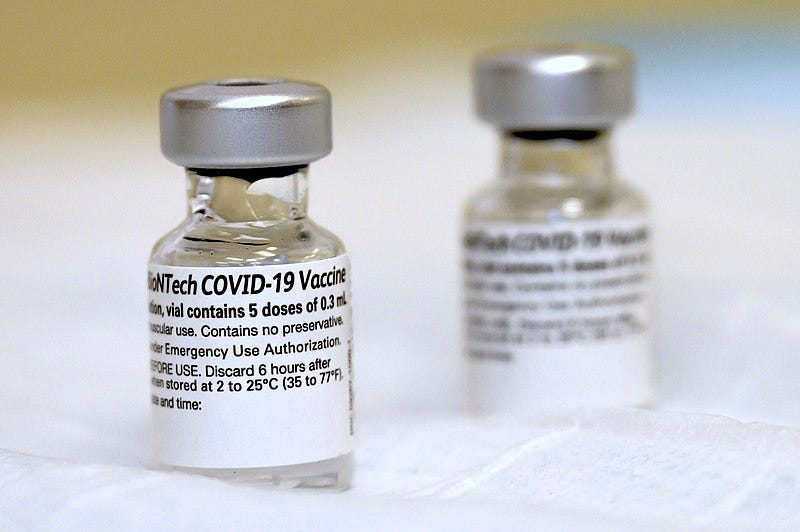

Though it was undoubtedly a game-changer, the scientific community still remained mostly uninterested in Weissman's and Kariko's work. But in 2010, their research caught the attention of two biotech companies: American company Moderna and German company BioNTech. Nine years later, when the first reports about COVID-19 appeared in the news, the companies immediately put the scientists’ research to use.

Dream big, reach higher

And that's how, after over 20 years of constant research, scientific struggle and hard work, an mRNA-based vaccine was developed.

It’s the first vaccine that doesn’t use an actual virus to cause an immune response. Instead, according to Health Canada, it teaches your body how to make proteins and, as a result, create antibodies to fight the potential infection.

In the first clinical trials, the vaccine showed 95% effectiveness, and in December 2020, Weissman and Kariko received their first shots at the University of Pennsylvania.

Though highly efficient, just like every vaccine, the COVID mRNA vaccine has some potential side effects.

“Common side effects include fever and chills. Among the more serious ones are Myocarditis and Thrombosis, but it happens on really rare occasions,” says MD Dr. Thomson, a physician from California.

On the bright side, she notes there is the possibility that mRNA vaccines can form longer immunity than natural infection.

Today, the mRNA COVID-19 vaccine is one of the most popular and, more importantly, effective vaccines out there. The success brought recognition to everybody who played a key part in its advancement, including Dr. Weissman.

He admits it's been difficult for him to handle all the press attention that came with fame, as he's a shy and quiet person. Nevertheless, it warms his heart to see people's gratitude from all over the world.

“You’ve made hugs and closeness possible again,” said one of the postcards mailed to his office in Philadelphia.

Weissman's biggest advice to all the young scientists, who only start their journey in the field, is to never give up.

“Most science is setbacks and difficulties, but it gives you an enormous amount of freedom and room to explore. So with enough perseverance, you can achieve anything you want.”

Related reading

Penn Medicine: The Story Behind mRNA COVID Vaccines

5-minute video interview of Weissman and Kariko

They discuss the beginning of their friendship and collaboration and do some ‘‘behind the scenes’’ of Pfizer's development.

The video gives us additional insight into their working process and shows the scientists from a human side, so to speak.

The New York Times: Kati Kariko Helped Shield the World From the Coronavirus

This article is focused on the life and work of Weissman’s colleague-Katalin Kariko

It talks about Kariko’s story and not just as a scientist-as a person. It takes a dive into her family life, her struggles to find work, her early career.

We get to see mRNA research work from Kariko’s perspective which is interesting to read after getting to know Weissman’s.

WSJ: Vaccine Side Effects: What to Expect After Your Covid-19 Shot

This is a 5-minute video discussing the side effects of mRNA vaccines.

It explains the nature of each side effect, talking about both normal and abnormal ones.

It contains commentaries from health experts, as well as common people, sharing their views about the vaccines.

In short, the video has both a professional and public outlook on the vaccines and is one of a few that talks more or less in depth about another side of Pfizer.

Health.com: No, the COVID-19 Vaccine Won’t Make a Magnet Stick to Your Arm-Here’s What’s Really Going On

It’s an article focused on debunking one of the myths about COVID-19 vaccines-that it makes a magnet stick to your arm.

The article is a mix of fun and science: since this myth started spreading from a TikTok challenge, the piece contains a few video examples from the platform, as well as what the healthcare experts say about it.

Compared to the material presented above, this article discusses an unusual question and overall has a lighter tone.

About the author

My name is Oleksandra Chorna, I’m an international student from Ukraine.

Right now, I’m in my third year of the Bachelor of Journalism program.

I’m passionate about writing and storytelling.